Himalayan Balsam: A Prohibited Noxious Weed

by Aislinn Case & Brett Kerley

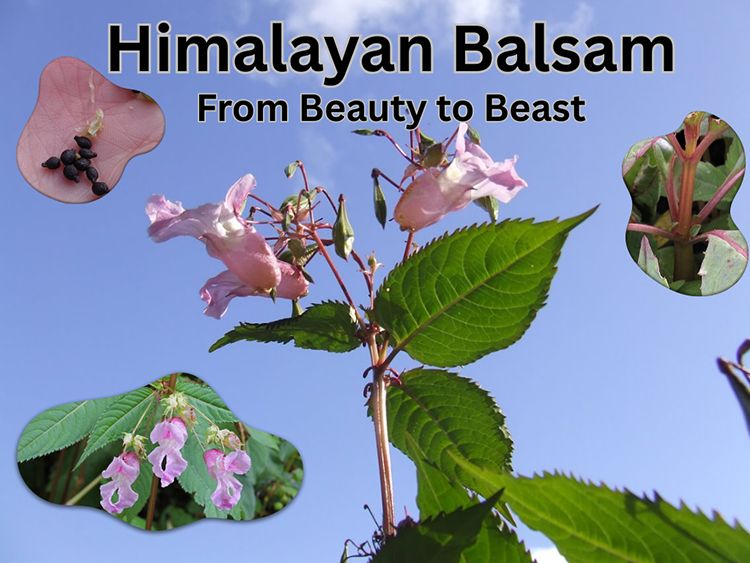

Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) may look like a gardener’s dream with its tall stature, bamboo-like stems, and orchid-shaped pink flowers, but in Edmonton, it’s becoming a nightmare for our natural spaces.

Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) may look like a gardener’s dream with its tall stature, bamboo-like stems, and orchid-shaped pink flowers, but in Edmonton, it’s becoming a nightmare for our natural spaces.

Native to the Himalayas, this annual plant has spread aggressively across Europe and now appears in scattered infestations throughout Alberta — including several along the North Saskatchewan River valley and smaller creeks.

Its beauty hides a dangerous side: prolific seed dispersal, fast growth, and the ability to smother native plants. In Edmonton’s fragile riparian zones, Himalayan Balsam can destabilize banks, reduce biodiversity, and permanently alter plant communities.

Identification

Himalayan Balsam is easy to spot if you know what to look for:

- Height: 1–2.5 m (3–8 ft) by mid-summer, towering over most native wildflowers.

- Stems: Hollow, smooth, and reddish-green, snapping easily when bent — similar in texture to bamboo but without the hardness.

- Leaves: Lance-shaped, sharply serrated edges, typically arranged in whorls of three.

- Flowers: Pink to purple, orchid-like blooms with a hooded shape, appearing June–October.

- Seed pods: When mature, these pods explode on contact, flinging up to 800 seeds per plant as far as 7 m (23 ft).

In Edmonton, it’s often found in moist, nutrient-rich soils along rivers, creeks, stormwater ponds, and shaded ditches — particularly in areas disturbed by human activity or flooding.

Himalayan Balsam flowers

Himalayan Balsam seeds

Why Himalayan Balsam is a Problem

- Riverbank erosion – Our North Saskatchewan River and its tributaries already face seasonal erosion. Himalayan Balsam’s shallow roots pull out easily, leaving bare soil that washes away in spring melt or heavy rain.

- Biodiversity loss – It forms dense stands that crowd out native plants like wild bergamot, goldenrod, and prairie clover, depriving pollinators of diverse food sources.

- Seed spread by water – Seeds float, making the river a conveyor belt for infestations downstream.

- Rapid colonization – Once a seed bank is established, it only takes one season for a new infestation to dominate an area.

Control Strategies

Manual Removal (Best for small infestations or sensitive sites)

- Pull by hand – Most effective when soil is moist, usually in late spring to early summer before flowers appear. Grasp near the base to ensure the whole root comes up.

- Cutting or strimming – Cut at ground level in May or June, before flowering. In Edmonton, regrowth can occur in warm summers, so a second cut in July may be necessary.

- Bag and remove plants – Never compost Himalayan Balsam; seeds can mature even after the plant is cut. Double-bag and take to the Eco Station.

Chemical Control (For large infestations)

- Herbicides like glyphosate (Round-Up) or 2,4-D amine (Weed-Be-Gone or Killex) can be used where mechanical removal isn’t feasible, but:

- Avoid spraying near water without proper permits.

- Only certified applicators should treat riparian zones under Alberta’s Pesticide Sales, Handling, Use and Application Regulation.

- Replant with natives immediately after treatment to prevent other invasive species from moving in.

Biological Control

- The rust fungus Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae has shown promise elsewhere, but Alberta trials are limited. Its survival in Edmonton’s freeze–thaw cycles is unproven.

Prevention

- Early detection – Check high-risk sites in spring and summer: riverbanks, shaded trails, and disturbed soil along construction areas.

- Clean equipment and clothing – Seeds cling to boots, pet fur, bicycle tires, and mowers. Brush off and wash before leaving infested sites.

- Community reporting – Suspected plants can be reported to the City of Edmonton’s Pest Management or Alberta Invasive Species Council.

- Educate neighbours – Many infestations start from ornamental plantings gone wild. Ensure local gardeners know it’s prohibited in Alberta under the Weed Control Act.

Plant These Instead!

(All plant info based on Edmonton’s Canadian Zone 4/USDA Zone 3a)

For Pollinators

Fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium)

- Zone: 2–7

- Height: 90–180 cm (36–72 in)

- Spread: 30–60 cm (12–24 in)

- Bloom Time: July–September

- Notes: Tall, upright perennial with striking pink–purple flower spikes. Thrives in full sun and disturbed soils. Great for naturalized areas but can spread by rhizomes, so give it space or plant in controlled beds.

Western Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

Western Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

- Zone: 3–9

- Height: 60–120 cm (24–48 in)

- Spread: 45–90 cm (18–36 in)

- Bloom Time: July–August

- Notes: Aromatic, drought-tolerant, and resistant to deer. Flowers are pale lavender to pink and attract bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds. Prefers full sun to part shade in well-drained soil.

Showy Milkweed (Asclepias speciosa)

- Zone: 3–6

- Height: 60–120 cm (24–48 in)

- Spread: 30–60 cm (12–24 in)

- Bloom Time: June–July

- Notes: Essential for monarch butterfly caterpillars. Pale pink star-shaped flowers with a sweet fragrance. Does best in full sun and sandy to loamy soil. Avoid overwatering; it’s drought-hardy once established.

For Riverbanks & Moist Soil

Purple Prairie Clover (Dalea purpurea)

- Zone: 3–8

- Height: 30–90 cm (12–36 in)

- Spread: 20–45 cm (8–18 in)

- Bloom Time: July–August

- Notes: Deep taproot helps with erosion control. Purple flower spikes attract native bees. Prefers full sun and well-drained sandy or clay loam soils.

Marsh Marigold (Caltha palustris)

- Zone: 2–7

- Height: 30–60 cm (12–24 in)

- Spread: 30–60 cm (12–24 in)

- Bloom Time: May–June

- Notes: One of the first perennials to bloom in spring. Thrives in standing or slow-moving water and saturated soils. Great for pond edges and wet ditches.

Joe-Pye Weed (Eutrochium maculatum)

Joe-Pye Weed (Eutrochium maculatum)

- Zone: 3–8

- Height: 120–200 cm (48–80 in)

- Spread: 60–120 cm (24–48 in)

- Bloom Time: August–September

- Notes: Tall, statuesque plant with clusters of mauve–pink flowers loved by butterflies. Prefers moist, rich soils in full sun to light shade. Works well at the back of a border or in naturalized riverbank plantings.

These plants are available through Edmonton nurseries specializing in native species or community plant exchanges. Also check out ALCLA Native Plants or Edmonton Native Plant Society for more information and ideas.

Final Thoughts

In Edmonton, Himalayan Balsam is more than a pretty face — it’s an ecological bully. Once it takes hold, it can strip riverbanks of native plants, accelerate erosion, and turn biodiverse meadows into monocultures.

The key to beating it here is acting early, removing completely, and replanting with strong native competitors. Every plant you pull before seed set prevents hundreds of future invaders from washing downstream.

And remember — when it comes to invasive plants in Edmonton: Be ruthless, bag it, and replace it with something better.

The bees, the riverbanks, and future generations of gardeners will thank you.